INCENTIVES

Incentives and risk: the crucial motivators and obstacles to innovation

Incentives drive innovation. The way individuals are incentivised, and how outlook and behaviours are recognised and rewarded or penalised, is perhaps the most difficult Innovation Dimension to get right, yet has the capacity to vitiate all other aspects of innovation.

Small, high growth businesses have a huge advantage from invariably being formed from people who are already motivated by innovation with a common aim, a win-win outlook and passionate leaders. Unfortunately, larger organisations face many endemic obstacles to successful innovation. This discussion therefore focuses on innovation incentives in larger organisations. The language tends to be in terms of companies, but the issues and approaches relate equally to public sector organisations with some tuning of the details.

This area of innovation incentives is one of the most immature areas in both innovation management and innovation governance. It is inextricably linked to risk and opportunity management, and to the overall risk appetite of the organisation. There have been few definitive publications on this aspect, and dilemmas and contradictions with established incentivisation practice abound.

Whereas there is a broad consensus that innovation is the key to future value creation, instinctive risk aversion and systemic reluctance to embrace imaginative opportunities, or understand pivotal risk scenarios, tend to make practice much less conducive to innovation than headline commitments might suggest.

Innovation Incentives Issues:

- If external targets are short term, how to incentivise internal strategic behaviours. Most organisations, especially publicly quoted companies, are hostage to short term performance and market sentiment. In principle, markets should give as much weight to innovation governance credentials of companies as to short term results, especially as market sentiment leans towards future prospects, discounting what is known today. Despite this, analysts seem not to be focused on such strategic dimensions. So while good CEOs will emphasise their organisation's growth and innovation potential in news flow, they have to be driven by the impact of the latest results. Delivering short term results whilst building the long term story is the mark of the successful CEO. This means CEOs have a vital role to translate external targets into an internal incentive structure in a way that compensates for, rather than just passes down, market myopia, whilst still driving delivery of near term expectations. It implies a more subtle approach to incentives than the common convention that shuns a differences between external and internal targets. It means internal targets must give weight to longer term indicators, such as growth, competitiveness, and indicators of innovation pipeline and potential such as the shadow innovation balance sheet outlined below. Multi-year vesting for annual bonuses to penalise managers who raid the future to meet today's targets is also relevant to innovation culture, as it is to many other aspects of corporate motivation.

- Incentivise Middle Managers to foster innovation. Middle managers have a profound influence on innovation culture, and have the closest control of allocation of resources. Sometimes it will be right to deliver current performance even if this compromises the future, but normally manages must find a way to do both. Incentives must capture the need to deliver to both objectives. As always, incentives should avoid being linked to input measures even though these tend to be more measurable, but look to outcome goals (or to intermediate goals that relate directly to outcomes). Exactly how incentives should be constructed needs to reflect the business context, but typical features could include:

- Tailored innovation target related to medium term outcomes, for example achieving higher growth or lower costs over a 3-5 year period, or delivering on specific innovation projects/initiatives.

- Maintaining a medium term strategy that sets out how key opportunities are captured, and also how key risks are being mitigated.

- A personal target set around supporting innovation across the business, eg in other middle managers' businesses, support for ideation workshops, quality of analysis feeding corporate strategic planning activity. This kind of assessment can be made through 180/360 degree assessments.

- Recognition for ideators and innovation teams. People who create novel ideas should be seen as heros to be role models for others. Likewise, teams who have successfully prosecuted an innovation outcome should be recognised as special contributors. Recognition may involve a modest financial reward, or focused on 'soft' recognition such as awards, internal PR, or allocation of uncommitted time to follow new ideas. Recognition for initiating an idea that goes on to be a success should be made even if that individual or team did not participate in the full development. This is important as initiators of ideas are often not the right people to develop them, but they should still get the kudos from the original act of conceiving an idea that did not exist before.

- How to treat innovation projects that fail or terminate. This is very important. If the people involved in an innovation project are penalised if their idea fails, when they have executed well and been through all the gates honestly, others will get a negative message message and potential innovators will retrench or leave for elsewhere. If an innovation project is not working out, it should be seen as creditable to re-consider or abandon, not to plough on when termination or re-direction is needed. This is why rigorous gates and a shared understanding of risks and returns is so essential. While a less than successful outcome cannot be hailed as a great achievement, if the innovation process and gate approvals have been sound, the risk/return judgements made should be robust to hindsight. Teams that recognise problems early, seek support to rectify them, but step back openly when the risk/return position goes adverse, should be given strong recognition, not have black marks against their careers. Conversely, where there has been a lack of rigour or openness, or where poor innovation practice has been adopted, sanction is always justified.

- Internal Entrepreneurship. Innovation teams can be set up as a spin-out, either formally as a separate legal entity, or by some internal shadow corporate entrepreneurship structure, giving innovators a direct incentive as stakeholders in the separated entity. This is a powerful motivator and has led to many successes. In fact, many of the highest growth startups have been formed by teams being carved out of existing larger enterprises (see, for example, the historical accounts of Silicon Valley). Teams that have been nurtured in an existing company start with experience, knowledge of the the routes to market, good access to complementary assets and probably an idea that is more mature. There is evidence to suggest that an internal spin-out approach, where the people remain employees of the parent, is much less successful, although the idea of capturing small business entrepreneur behaviour within a larger business is beguiling. At the moment this remains an area needing further research, but there does seem merit in the basic approach of an organisation looking favourably on an entrepreneurial team forming a new entity, giving it support and taking an equity return.

- 'Innovation Balance Sheet' Portfolio Analysis. Normal accounting practice will only take innovation investment costs onto the balance sheet when some tangible evidence of future revenue is available. Liberal capitalising of research and innovation is highly risky and is rightly only undertaken when there is a well founded route to future profitability. To compensate, it is possible to maintain a shadow 'balance sheet' of expensed innovation costs and potential returns, supported by scenario analysis of alternative external contexts by some form of Monte Carlo analysis of outcomes. This can be used to give a running assessment of the health of an innovation portfolio and highlight movement in what can be seen to be a rolling portfolio NPV. This can be a powerful way to give some look forward for businesses innovation strategy.

Innovation Governance Checklist

- Are internal targets designed to balance short term performance with medium term growth

- Is there a means to assess innovation potential of a business unit by some form of 'innovation balance sheet?

- Is there a map of recognition events that make heros out of people who create successful new ideas?

- Does the incentive regime encourage innovators to take agreed risks without penalty if declared risks accrue?

- Are middle mangers recognised for balancing short term performance and strategic gain?

- Is there opportunity for corporate entrepreneurship?

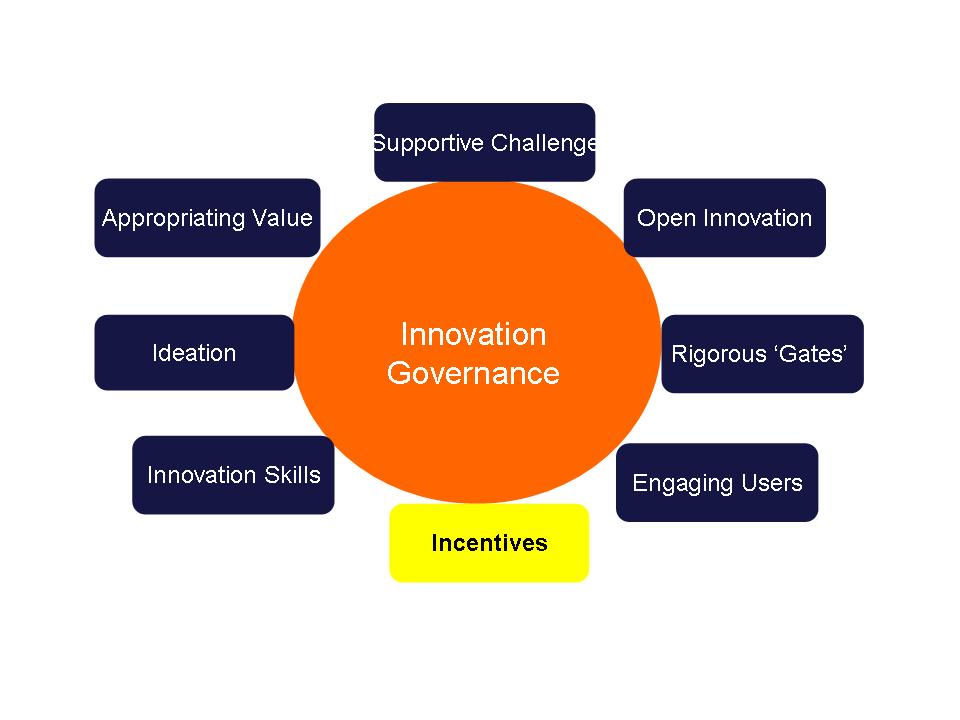

Back to Innovation Dimensions

|